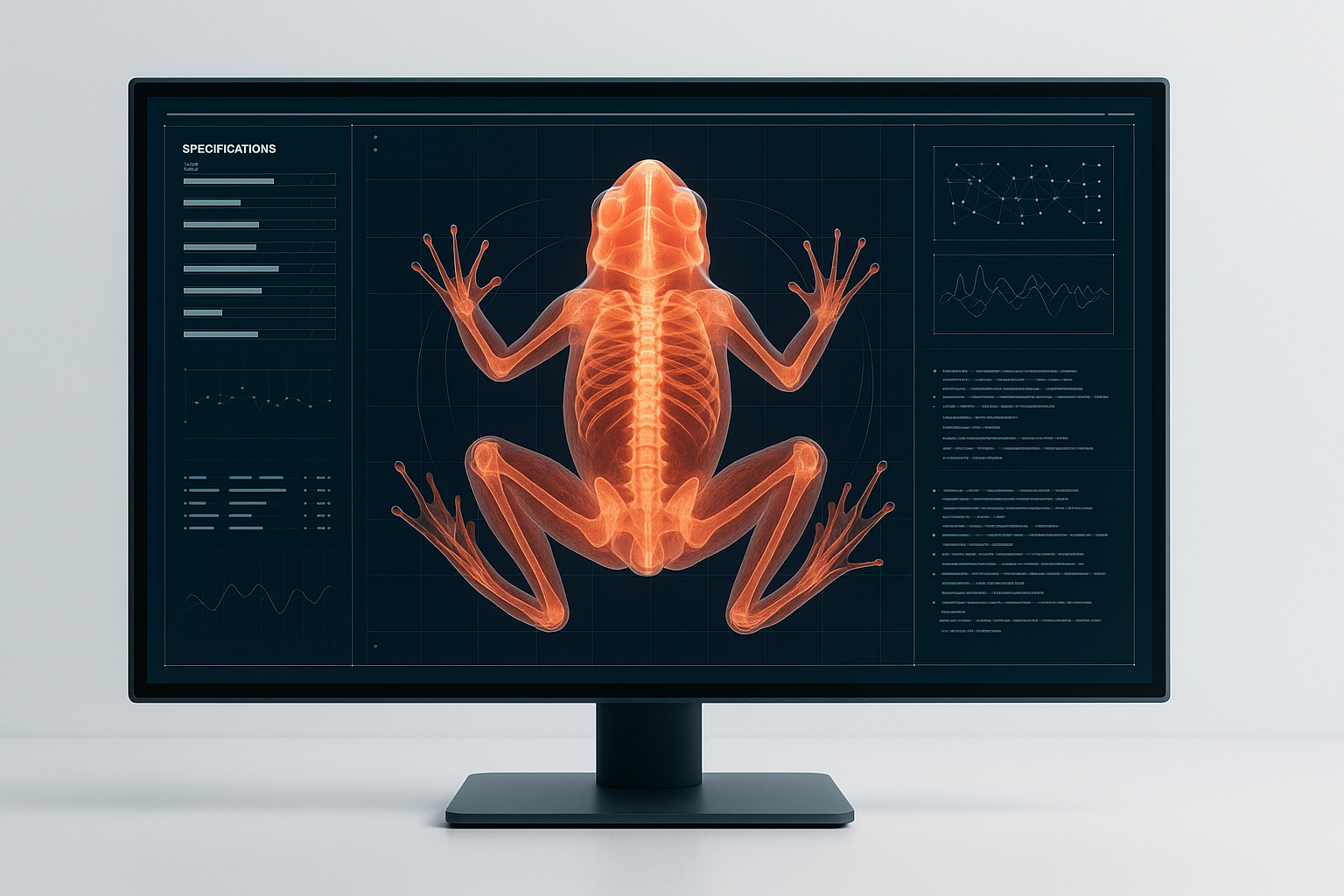

Anatomical Compiler

Computational system for designing biological forms by specifying desired anatomical outcomes and automatically generating bioelectric interventions needed to achieve them.

The Anatomical Compiler represents a conceptual computational framework proposed by Michael Levin for rational design of biological morphology. Drawing inspiration from software compilers that translate high-level programming languages into machine code, the anatomical compiler would translate desired anatomical specifications into specific bioelectric and molecular interventions required to produce those forms—enabling systematic morphological engineering beyond trial-and-error approaches.

The anatomical compiler concept addresses a fundamental challenge in bioengineering: how to rationally design living forms rather than randomly searching vast parameter spaces. Traditional approaches require: exhaustive trial-and-error testing countless genetic modifications; decades of research to understand specific developmental pathways; inability to predict emergent outcomes from molecular changes; and limited success producing desired morphologies. The anatomical compiler instead proposes: specifying desired anatomical outcomes at high level (e.g., 'six-legged frog'); computational translation of anatomical goals into required bioelectric patterns; automatic generation of intervention protocols achieving those patterns; and predictable morphological outcomes from computed interventions.

The compiler concept treats morphogenesis as a programmable biological computation where

genetic and bioelectric networks execute developmental programs; cellular collectives process information to build target morphologies; anatomical outcomes emerge from coordinated cellular decision-making; and interventions can reprogram developmental goals by changing instructional signals. This views organisms as programmable systems with morphological plasticity rather than genetically fixed forms.

An anatomical compiler must bridge multiple biological scales including

genetic networks determining cell behavior and protein expression; bioelectric patterns encoding positional information and morphological goals; cellular mechanics and movement during morphogenesis; tissue-level forces and constraints shaping organs; and organism-level anatomical constraints determining viable forms. The compiler would integrate these scales into coherent predictive models.

The compiler would accept anatomical specifications in various forms including

target morphology descriptions (e.g., 'planarian with two heads'); quantitative anatomical measurements (organ sizes, limb positions); functional requirements (e.g., 'organism capable of navigating maze'); constraint specifications (biocompatibility, viability requirements); and species context determining baseline morphology. This provides a design interface abstracted from molecular implementation details.

The core compiler function involves parsing anatomical specifications into quantitative morphological parameters; mapping parameters to required bioelectric patterns via developmental models; computing bioelectric pattern differences between current and target states; identifying ion channel and genetic interventions producing required pattern changes; optimizing intervention sequences for efficiency and viability; and outputting executable biological protocols. This translation automates the design-to-implementation pipeline.

The compiler requires comprehensive databases mapping morphologies to bioelectric signatures including

voltage patterns associated with specific anatomical structures; bioelectric determinants of organ size, number, and position; species-specific bioelectric-morphology relationships; temporal dynamics of pattern evolution during development; and intervention-outcome relationships from experimental data. These libraries enable predictive morphological programming.

Current approaches toward anatomical compilation use evolutionary algorithms including

computational simulation of developmental processes; fitness evaluation against desired morphological outcomes; iterative refinement through simulated evolution; and translation of successful virtual designs into biological implementations. Xenobots exemplify this approach—computationally evolving cell configurations then building the physical organisms.

The compiler must ensure designed organisms remain viable considering

biophysical constraints on possible morphologies; developmental feasibility given available cellular mechanisms; metabolic and physiological viability of resulting forms; ecological and evolutionary plausibility; and safety considerations for engineered organisms. The compiler would reject or modify specifications violating critical constraints.

While the full anatomical compiler remains aspirational, key capabilities already exist including

bioelectric pattern manipulation producing predictable morphological changes (planarian head shapes, frog limb regeneration); computational modeling predicting morphological outcomes from voltage changes; xenobot design demonstrating computational morphology-to-implementation pipeline; and ion channel intervention protocols producing specific anatomical alterations. These components provide proof-of-principle for compiler feasibility.

Levin frames the anatomical compiler through cognitive and computational analogies

cells as agents processing information and making decisions; tissues as cognitive systems storing and retrieving morphological memories; bioelectric patterns as 'thoughts' of the tissue about target morphology; and interventions as persuasion rather than micromanagement—convincing cellular collectives to build different structures. This cognitive metaphor informs compiler design.

An operational anatomical compiler would enable numerous applications including

custom organ engineering for transplantation with specific size and properties; regenerative medicine programming replacing lost or damaged structures; synthetic organism design creating novel forms for specific functions; developmental disorder prevention and correction; agricultural optimization designing improved crop morphologies; and fundamental research testing hypotheses about morphological determinants. The compiler would democratize morphological engineering.

Compared to conventional genetic engineering and stem cell approaches, anatomical compilation offers

morphological-level design abstraction avoiding molecular micromanagement; predictable outcomes from specified goals rather than trial-and-error; intervention at bioelectric level without permanent genetic modification; faster design iteration through computational prediction; and working with cellular intelligence rather than overriding autonomous programs. This leverages biological computation rather than brute-forcing desired outcomes.

Developing a full anatomical compiler faces significant challenges including

incomplete understanding of morphology-bioelectric mappings across species; computational complexity of multi-scale developmental modeling; species-specific differences requiring extensive training data; unpredictable emergent behaviors in complex biological systems; ethical considerations around morphological engineering capabilities; and validation requirements ensuring designed organisms are safe and functional. Current research addresses these systematically.

The anatomical compiler exists as

conceptual framework guiding research programs; partial implementation in xenobot design pipelines; experimental proof-of-principle demonstrations for specific morphological changes; growing databases of bioelectric-morphology relationships; and improving computational models of development and regeneration. Progress is transitioning from concept to operational capabilities in limited domains.

Advanced compiler development will likely leverage

machine learning discovering bioelectric-morphology relationships from data; computer vision analyzing morphological outcomes for feedback; reinforcement learning optimizing intervention strategies; neural networks modeling complex developmental dynamics; and large-scale simulation incorporating diverse biological data. AI can help address the complexity challenges inherent in morphological compilation.

Key questions for anatomical compiler development include What is the appropriate 'programming language' for specifying morphologies? What level of abstraction optimally balances expressiveness and implementability? How can the compiler handle emergent properties and unpredictable outcomes? What safety mechanisms prevent unintended morphologies? How do we validate compiled protocols before biological implementation? Research continues addressing these fundamental questions.

The anatomical compiler concept has profound implications including

treating morphology as programmable software rather than genetic hardware; viewing organisms as executing developmental programs editable like computer code; suggesting anatomical space is more accessible than genetics alone would predict; implying morphological plasticity and evolvability exceed conventional expectations; and reframing biological design as information engineering rather than purely molecular engineering. This challenges reductionist views of biology.

Morphological programming capabilities raise ethical questions including

What forms should we design and for what purposes? Who decides acceptable morphologies for engineered organisms? How do we prevent misuse for harmful purposes? What regulations govern morphological engineering? How do engineered organisms relate to natural biodiversity? What are rights and welfare considerations for novel forms? The field must develop ethical frameworks alongside technical capabilities.

The ultimate anatomical compiler would enable intuitive morphological design interfaces accessible to non-experts; reliable translation from specifications to implementations; rapid prototyping and iteration of biological forms; integration with synthetic biology and genetic tools; closed-loop refinement based on outcome assessment; and expanding from simple organisms to complex tissue engineering. This would constitute a morphological design revolution comparable to CAD/CAM in mechanical engineering.

The Anatomical Compiler concept represents a fundamental reconceptualization of biological engineering—from molecular micromanagement to morphological programming, from genetic determinism to bioelectric control, and from trial-and-error to rational design. By treating morphogenesis as programmable computation, the compiler framework suggests that biological form is more plastic and accessible than previously understood, that organisms can be designed at the anatomical level rather than only genetic level, and that morphological engineering may become a practical discipline. While not yet fully realized, the concept guides cutting-edge research synthesizing developmental biology, bioelectricity, computation, and synthetic biology toward revolutionary morphological control capabilities.

Follow us for weekly foresight in your inbox.